The South China Sea: The Promise Below Troubled Waters

There’s no gainsaying the risks in the strategic competition in the South China Sea. A new book suggests cooperation beneath its surface could chart a different course.

The news doesn’t lack for stories recounting the great and small power rivalries roiling the South China Sea.

From China’s unilateral, illegal claim to its 1.4 million square miles and decades of building and militarizing artificial islands atop its fragile shoals to disputes among littoral states over contested reefs and resources, the tensions are real. So, James Borton argues, is the possibility to solve shared problems and lessen the strain.

President Trump’s Defense Secretary made more than passing reference to Asia’s troubled waters at the Shangri-La security conference last month when he highlighted Beijing’s offshore ambitions. War over Taiwan, Pete Hegseth intoned, could break out any time. American military plans are giving Asia priority, he said, but Asians need to spend more on defense if they want US help to confront China’s threat.

Hegseth, of course, was hardly delivering new news to the region’s leaders. China’s military power and assertiveness is a growing concern, and from Tokyo to Manila and Canberra, US allies are closing ranks. That said, defense cooperation with Washington elsewhere in Asia is far shallower. If Hegseth’s monocular focus on muscling up militarily is the administration’s solution, it’s likely to stay that way.

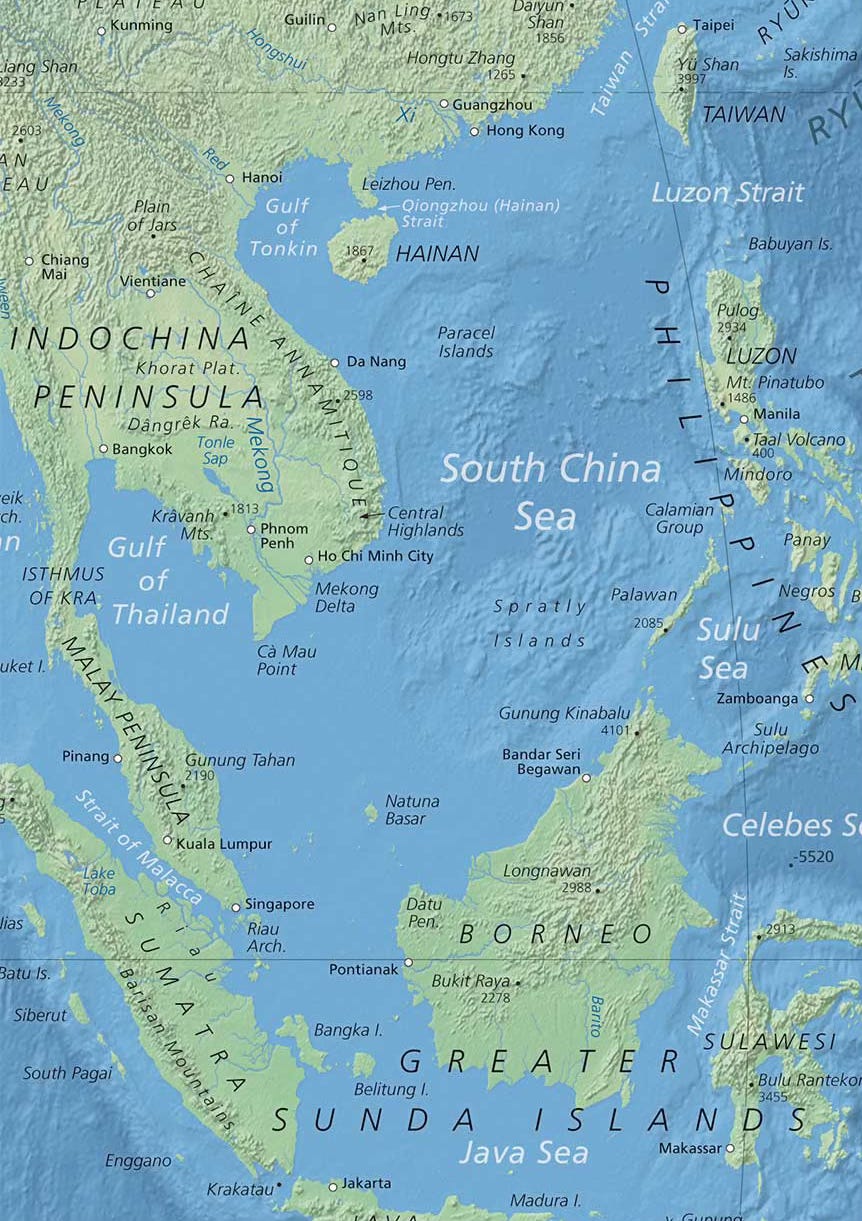

The array of issues surrounding the South China Sea shows why. Let’s stipulate that its strategic importance is hard to overstate. Roughly a third of all global trade, some $4 trillion in value in 2024, transits its waters. The importance of that share spikes for China, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea—as it does for the world—given the quartet’s central role in manufacturing products vital to the global technology ecosystem.

For Asians, however, trade routes only begin to describe why the South China Sea matters. Most obviously, it’s a vital source of food supplies for the 600 million people in Southeast Asia as well their neighboring 1.4 billion Chinese. Fishing is central to local economies, but the competition is tough. Nearly two-thirds of the world’s fishing vessels work the waters, hauling twelve percent of the world’s fishing catch.

Energy rights and problems are no less an issue. According to a US Energy Department report last year, while some 3.6 billion barrels of proved and probable oil and gas reserves are in territorial waters, conflicts have impeded development of even more potentially exploitable resources. DOE estimates 2.4-9.2 billion barrels of oil and other liquids, plus natural gas are under disputed waters offshore.

Harvesting the Waves, a new book by James Borton, acknowledges the contention, but unlike Hegseth’s call-to-arms, its author argues resolving the problems below the South China Sea’s surface, rather than revving up the rivalries atop, is an opportunity to build cooperation. Unfortunately, his subject matter is one where the Trump administration is literally at sea.

Borton’s focus is the mounting dangers to the ecology of the South China Sea where the territorial disputes impeding cooperation are raising the environmental stakes for all concerned. Only shared solutions, he writes, can protect one of the world’s most unique and vital eco-systems. In Harvesting the Waves, Borton provides a detailed presentation of the possibilities using science as the tool.

A foreign correspondent, Asia hand, and senior fellow at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies’ Foreign Policy Institute, Borton has more than a toe in these waters. His 2021 book, Dispatches from the South China Sea, examined coastal development, overfishing and reef destruction in a fascinating story of fishermen and scientists dedicated to preserving the sea’s life and ecology.

Harvesting the Waves points to developments over decades—from the Law of the Sea Conference and Bali Congress in the 1980s to recent studies on protecting Asia’s threatened marine biodiversity—that have laid a foundation for broader collaboration. In the South China Sea, the challenges such as declining fish stocks, dying reefs and pollution are no secret, nor, Borton makes clear, are the inadequate responses to date.

A study 15 years ago by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN) Center for Biodiversity provides a telling example of the limits on what individual countries have done. “Among 152 coastal and marine key biodiversity areas that have been identified in ASEAN members’ territories,” Borton writes, “only 35 were protected, 20 partially protected and the rest are not protected at all.”

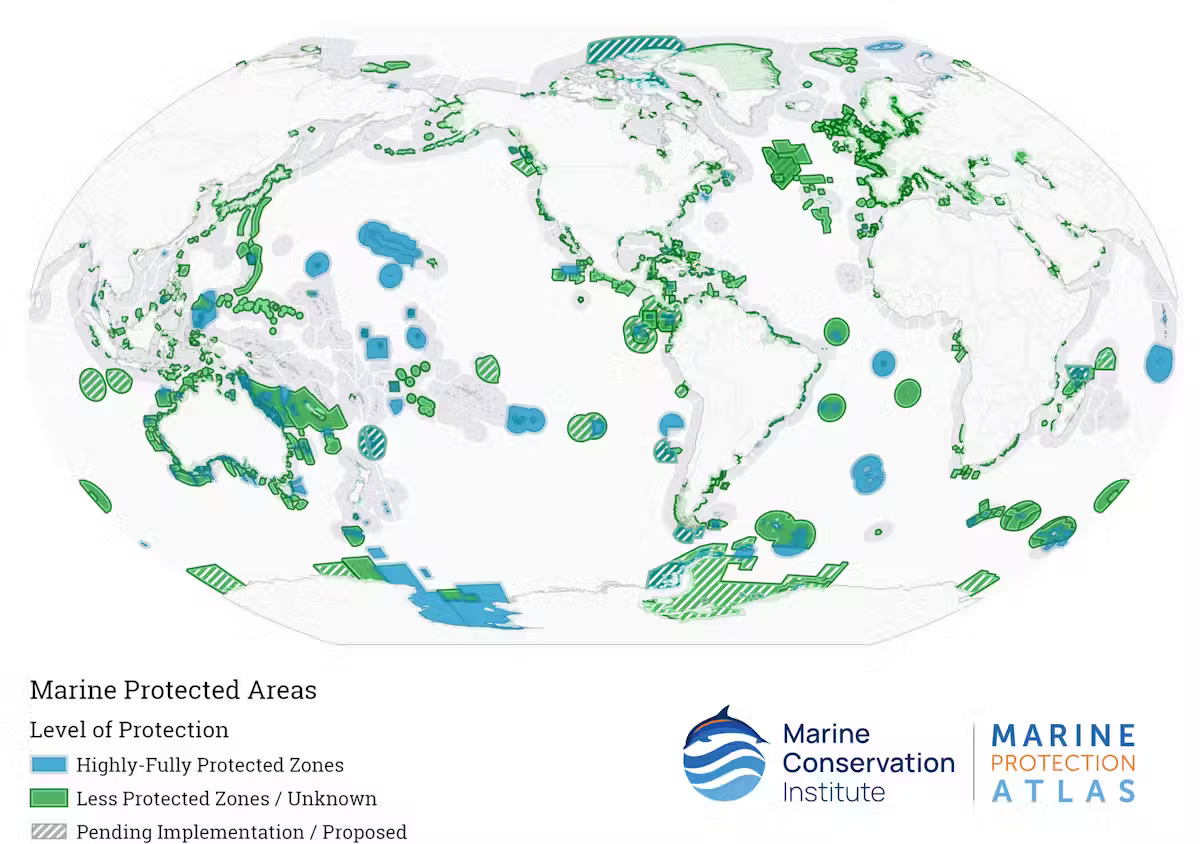

Borton asserts that a science-based approach to expanding and managing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) is the solution. MPAs restrict and regulate fishing, mining, and tourism to conserve biodiversity, replenish fish stocks, and protect ecosystems. Their safe havens allow marine life to thrive and ecosystems to recover. Whatever the shortcomings, their success elsewhere, he argues, shows they’re not pie-in-the-sky.

The Mediterranean Sea is the case in point. In its historically contested waters, MPAs have led to major advances in protecting its habitat and biodiversity. Created in 1976 by Barcelona Convention, an international accord that aimed to limit as well as abate pollution, the Mediterranean Action Plan (MAP) has undergirded a networked management of MPAs, promoting cooperation to save a shared maritime heritage.

Harvesting the Waves is well timed. In Nice this month, the UN Conference on the Oceans pushed to advance a high seas treaty aiming to expand protection to the 97 percent of the world’s oceans, the “high seas,” vulnerable to destructive exploitation. Drafted in 2023, the treaty is moving ahead, now only 11 votes short of the 60 nations required for ratification.

More to Borton’s point, 30 new Maritime Protected Areas were announced at the UN conference. The news nonetheless underscored the challenge of adding MPAs in territorial as well as international waters. A study published in May found the average Marine Protected Area covers 10 square kilometers, testifying to the waters yet-to-go before the global goal of protecting 30 percent of the world’s oceans by 2030 is met.

That the Trump administration will see the political opportunities in supporting the kind of environmental efforts in the South China Sea described by Harvesting the Waves is more than doubtful. The US role as “observer” at Nice made that clear enough. But Washington isn’t just missing-in-action. Like his gutting of domestic environmental regulations, Trump also is rolling back restrictions in US MPAs.

In April, for example, Trump opened parts of the 500,000 square mile Pacific Islands MPA to commercial fishing and is suggesting he’ll do the same elsewhere. The u-turn isn’t an outlier. According to USA Today, the Trump administration’s budget cuts $32 billion from the agencies that monitor weather, oceans, and the atmosphere as well as protect natural and historic resources, parks and conservation lands.

Whatever Trump’s luddite legacy on the environment may be, one thing already is obvious. In the contest for comrades as well as cooperation in the neighborhood where Hegseth last month called for partners to challenge China, Beijing is moving smartly to capitalize on the collapse of US environmental engagement. Indeed, Borton’s impressively researched book is well timed in that sense as well.

Harvesting the Waves is optimistic, as was Borton’s commentary in the South China Morning Post last month. Borton argues science diplomacy, China’s version included, can bring wider collaboration, not only on environmental problems but in laying the groundwork for political cooperation as well.

Time will tell, of course, and there is much reason for skepticism over Chinese initiatives seeking to green-wash its illegal offshore territorial claims, sand grabs, and island-building ecological destruction.

When it comes to solving the mounting environmental challenges affecting the South China Sea, however, the simple fact is Beijing’s soft power is on display at the table and Washington’s is not. It’s an unforced error that needs to be corrected.

If it is, Harvesting the Waves provides a comprehensive, and thought-provoking view of what could be accomplished in this important region and how.

For China, as you suggest, Carl, Trump is the gift that keeps on giving. Today's news is the latest example reporting that the Japanese cancelled the 2+2 after Trump's DoD demanded a 3.5 percent of GDP level for Tokyo's defense spending. Aside from the lunacy of spitting in the eye of a leadership that has already committed to unprecedented spending increases despite its tenuous domestic political standing, you have the cumulative effect of a nonsensical trade war, threats of US troop withdrawals, and a president, barely coherent when he's at the table, that walks out on G-7 allies who want to talk. In Beijing, what's not to like? Just pour some more tea, sit back, and watch the clown show....

As always you present information that I should have focused on, but didn't.Thanks. From my perspective from the boon docks I see that instead of putting Beijing on its heals as they proclaim is their goal, instead the clown car and its driver have done everything they can to give Beijing a free ride. Sad.